For years the F1 quick lift jack was a simple humble tool used around the garage and at pit stops. Since pit stops have become an ever greater part of the team’s performance during the race, the jack has come in for increasing levels of development. As powered jacks are no longer allowed, teams rely on a hefty pull from a mechanic to lift the car and gravity to return the car to the ground. Improving this process has lead to most teams adopting a similar quick-release swivel jack. At first a complicated looking piece of kit, the jack is still a simple device when reduced to its component parts.

Category Archives: Generic Technical

Tech Files F1 : Technical side of F1 (Part3)

http://www.gocar.gr/en/races/f1-tech-files/

Part 3 of the Tech files is now available on GoCar.gr, covering the basics of the Front Wing; Multiple Elements, Cascades, Endplates, Flexing and DDRS

Analysis: F1 Fuel System

One of the great pieces of unseen technology in the F1 car is the fuel system. Comprised of complicated fuel tank and an array of pumps, the system is taken for granted. The super safe and highly efficient fuel system delivers the F1 cars 160kg of fuel during a race with barely any reliability issues.

Historically fuel tanks were simply metal tanks formed to fit in wherever they could be fitted. Often prone to puncturing during accidents and impacts, the fuel could easily spill and cause a huge fire. Major fires in F1 car are now thankfully rare. It’s fair to say the biggest leap in F1 safety has probably been the advent of the flexible fuel cell. Flexible bags to house the fuel have been part of the regulations for decades, There’s been no major fuel tank fire at an F1 race since Berger Imola crash in 1989 and no fire related deaths since Ricardo Palletti in Canada in 1982, or in testing with Elio De Angelis in 1986.

Anatomy

Fuel systems in F1 are split into two areas; the fuel tank itself and the fuel pump system that delivers fuel to the engine.

Gizmodo: Schumachers Seat

I’ve written a short piece for UK technology website Gizmodo on the features Michael Schumacher’s seat and cockpit.

InDetail: Caterham Front Upright

Not everything in F1 is aggressive, extreme, radical or innovative. In fact in many areas the car’s are very close in general design terms. Some times it’s enough just to soak up the detail engineering and explain what all the little bits and pieces do on the car. In this series of short articles, we’ll do just that, thanks to these amazing photographs from MichaelD. Following on from the details of the Force India front corner, with these photos of the Caterham in Melbourne, we can now see more of the upright design.

Upright

Caterham’s upright is fairly typical of most contemporary F1 designs. By regulation all F1 cars have to use Aluminum for their uprights. This one appears to be a fully machined or perhaps a cast part. Before the restriction to aluminum, investment cast Ti or MMC were common.

In format the upright is tightly fitted between the upper and lower ball joints and the two bearing for the hub. This design has been common in the past ten years, before that the upright tended to be a larger item with a large vaned housing for the bearing that would be the route for cooling air to reach the brake disc. Now teams route the cooling around the upright rather than through it. One exception of this design practice was Honda who routed the cooling air internally through an oversize hub. This design was dropped in 2010, as the design prevented the lower wishbone mount being as high the aerodynamicists wanted.

The upright creates part of the suspension geometry, with the distance between the upper and lower ball joints and the angle between them and the steering axis.

The first observation of a current F1 upright compared to any other racecar is the distance between the upper and lower wishbone joints. The upper joint is probably as high as the 13” wheel will allow, and then the lower wishbone is raised to near the wheels centerline. Having the mounts close together creates more loads in the wishbones and restricts space for a track rod to be mounted high up, with enough of a steering arm length to be efficient. This is a compromise forced by the aerodynamicists, who require the wishbones to be placed in the most beneficial position relative to the front wing upwash.

Due to the offset of the bulk of the upright from the steering axis, the design at first appears to offer a lot of King Pin Inclination (KPI), but closer examination of the ball joints shows them to be relatively normal for an F1 car. An increased KPI angle creates more camber change through steering.

We can see the upper ball joint (UBJ) that links the upright to the wishbone is created with a clevis bolted the upright. The wishbones outer end holds the spherical bearing. Shims between the clevis and the upright adjust the static camber. The lower ball joint (LBJ) is a fixed mounting and is not adjustable. We can see in the case of the Caterham that the lower end of the pushrod is mounted to the wishbone and the not upright. It joins near the spherical bearing in order to keep the bending load in the wishbone end to a minimum.

Adjustments

The steering rack is mounted low down on the front bulkhead and the track rod passes in line with the lower wishbone and attached to its own clevis on the upright. Adjusting camber also adjust steering toe angle, so any change in the camber shims will require a shim altered on the track rod arm. As the clevis is formed by the upright, the track rod arm is split, with the metal end fitting bolting to the carbon fibre arm, a shim in between this joint creates the difference I track rod length.

In between the track rod and lower wishbone is one of the two tethers to hold the wheel on in an accident; there appear to be plastic clips to hold the tether in place between the two parts.

Hub & Bearings

Rotating inside the upright is the front hub, or stub axle. This is a machined titanium part and sits on two bearings. Typically two sets of bearings are used one larger set outboard and a smaller set inboard. From the diameter of the upright you can see the differential in size is quite large. Bearing design is quite secretive, but commonly angular contact ceramic bearing are used. I was told that Honda, who used NTN bearings at the time, would have the bearing last two races and cost several thousand pounds each. Albeit this was at the time they used particularly large bearings to hold the oversize hub. The bearings are located in the upright and the hub and preloaded by the large castle nut visible inboard of the upright.

The hub is hollow and will have openings and pockets machined into it to reduce weight where stiffness isn’t required. The hub also forms part of the brake disc mounting system the wire eroded splined on the flange outboard of the upright mate to matching splines on the brake disc mounting bell. There are also drive pegs to locate the wheel. At the threaded outer part of the hub, the wheel retention system is removed. This is a sprung clip that flicks in\out as the wheel nut passes over it during wheel changes. The clip will retain the nut as required by the regulation, should the wheel nut not be tightened sufficiently. It will however not replace the function of the wheel nut in holding the wheel on securely. Drivers leaving the pits will see\feel the wheel wobble slightly, driving for too long will see the retention mechanism fail and the wheel fall off. Typically the hub and wheel nut threaded are handed left of right, to help keep the nut secured.

InDetail: Force India Front Corner

Not everything in F1 is aggressive, extreme, radical or innovative. In fact in many areas the car’s are very close in general design terms. Some time it’s enough just to soak up the detail engineering and explain what all the little bits and pieces do on the car. In this series of short articles, we’ll do just that, thanks to these amazing photographs from MichaelD.

This is the front left corner of the VJM05, seen without the wheel to expose the brakes, suspension mounts, hub and electronics. Details vary from team to team, but what we see here is typical of most F1 cars, indeed some of the components are standard (electronics) or lightly modified by the supplier (brakes).

Brake Caliper

Dominating the picture is the brake caliper. This is supplied by AP Racing and will be designed around Force India requirements, albeit based on their current iteration of an F1 Caliper.

F1 Bake calipers must have no more than six pistons, two pads and two mounting points. The material is restricted by an 80Gpa stiffness requirement; aluminum lithium is most commonly used.

AP have a unique design of caliper for many Formulii, with their RadiCal (Radical Caliper) design. This being the way the inner and outer sections join via the complex bridge structure, to make it as stiff as possible. We can see the caliper is bridged in two places and a radial brace is also used. Keeping his area open is important for cooling the brake disc.

Cooling is also behind the structure around the pistons, the cylinders the six pistons within are nearly completely exposed, with just some links to the calipers structure and internal passageway to route the brake fluid. This allows the most airflow around the cylinder\piston to keep them cool. The pistons themselves are made in titanium and have a series of radial holes machined into them to also keep heat from getting into the brake fluid.

We can see the brake line entering the caliper at the bottom, having been routed through the lower wishbone. At the top of the caliper are the two bleed nipples, these allow bubbles trapped within the system to float up and be removed for better brake feel.

The carbon panel on the outer section of the caliper is either an aero piece or some protection for the caliper when the wheels are slammed back on during pitstops.

Discs and Pads

F1 moved to Carbon discs and pads in the eighties, having moved straight from Cast iron discs. Strangely ceramic discs have not been a development seen at races. Rules limit the diameter and thickness of discs, but no other regulatory restrictions are placed on these parts.

Disc and pad material varies according to their manufacturer (Carbon Industrie & Hitco). It is also tuned for each race and even for each driver. Additionally cooling patterns will vary from track to track, For Force India in Melbourne we can see the high density drillings, with three small drillings across the disc. With Melbourne being heavy on braking the pads are also drilled in attempt to keep the brake system cool. Brakes and pads wear at an equal rate, so the few millimeters gap in between disc surface and drillings is all the wear these parts will see, before catastrophic failure. As wear increases with temperature there are sensors measuring the disc surface temperature and also wear sensors for both the inner and outer pads.

Electronics

To monitor all the functions on the front corner, there will be an array of sensors fitted to the parts. These are all linked back to the main SECU, rather than cabling for each sensor passing through the wishbones to the cars main wiring loom, there is a hub fitted to the upright that collects all he signals and passes them back via a single cable. This Hub Interface Unit (HIU) is a common part supplied by MES to all the teams. It has inputs from the aforementioned Pad wear and disc temperatures sensors, as well as two wheel speed sensor (two in case one fails), also a load cell for measuring pushrod (or pullrod) loads.

Wishbone mounting

Although the aluminum upright can barely be seen beneath the brake ducts, the key function of the upright is joins the hub to the suspension. F1 does not use adjustable suspension in the same way as many racecars. That is with threaded adjusters, but instead solid suspension links are mounted the hard points with shims. These shims are used to alter the camber, ride height, pushrod offset and castor.

Teams are no longer aligning the track rod for steering with the FTWB. So often the track rod needs a separate lower mounting point on the upright. When adjusting camber, a different FTWB shim will alter the steering toe angle, so an additional shim needs to be fitted to the track rod clevis t maintain toe angle.

In this picture, we can see the upper clevis that mounts the front top wishbone (FTWB) and track rod. Force India have done this with the VJM05, but have still been able to join the FTWB and track rod to the same clevis assembly. This way camber can be adjusted with a single shim, rather than separate but matched shims for separate clevises.

We can also see the extremely high front lower wishbone position (FLWB); it’s nearly at the front axle height. Having wishbones spaced further apart is better for reducing the loads fed through them, but aerodynamics demand a higher position. We can’t see the outboard joint with the upright; neither can we see the outer pushrod joint. It’s probably that FIF1 mount these mount to the upright in a set up called ‘pushrod on upright’ (POU), this helps eight transfer with steering angle in slow corners.

Tech Files F1 : Technical side of F1

Tech Files F1 : Technical side of F1.

I am collaborating with Greek F1 site, GoCar.gr. We are starting a series of features, that aim to explain F1 tech from the basics through to the detail of every system on the car; Aero, Mechanical, Safety and Driver Equipment.

We start with a simple view of the facts and figures and what we can see from the outside. Next we peel off the bodywork and explain some of the major mechanical parts.

For English click here : http://www.gocar.gr/en/races/f1-tech-files/t1,Technical_side_of_F1.html

Για Ελληνικά πατήστε εδώ : http://www.gocar.gr/gr/races/f1-tech-files/t1,Technical_side_of_F1.html

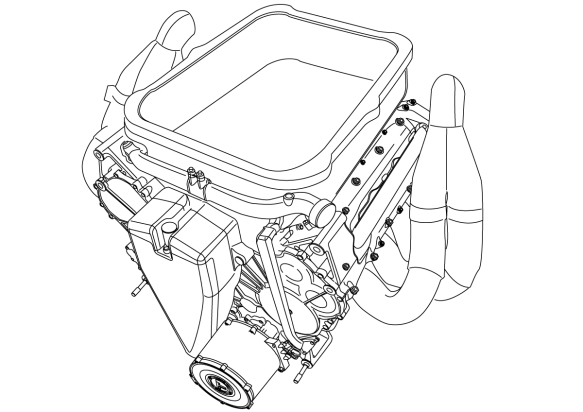

Mercedes AMG: Engine Build Challenge

During my visit to Mercedes AMG before Christmas, the company set us a challenge that’s been put to other more notable visitors. In the engine build area, two engines were arranged in each bay, but without the coil pack, heat shield and exhausts fitted. Our task was to fit these parts to one side of the engine, along with tightening each fastener to the correct torque setting. A dozen journalists attended the day, the challenge being made even greater as the two current Mercedes AMG drivers had also previously completed the challenge.

The first job was to fit the coil pack. The four-pronged carbonfibre cased unit is a press fit atop each spark plug, then the we needed to connect CAN electronics interface near the front of the airbox.

A small reflective coated carbonfibre heatshield goes over the coil pack, attached with three small bolts, one of which is smaller and requires a different torque setting.

Then onto the exhaust system, weighing about 3kg each exhaust is hand made from thin sections of inconnel welded together. Although the 4-into-1 exhaust is one assembly, there is some play in the primary pipes joints with the collector, so fitting the four exhaust pipes to the studs on the engine requires a little fiddling. Each exhaust pipe bolts to the exhaust port with three nuts, two above and to the side of the exhaust pipe, and one centrally below.

Each of these 24 nuts being tightened to the same torque setting. With the engine up on the stand and being able to kneel below the engine, getting access to each fastener was surprisingly easy, none of the exhaust pipes being particularly obstructive. I’m sure doing the same job with the engine in the car and the floor fitted is a very different story.

I completed the challenge in 4m 30s and I was satisfied I’d done a good job. However ex Racecar Engineering magazine editor, Charles Armstrong Wilson completed the challenge in an impressive 3m 30s! Even though one (un-named) journalist took as long a 7m 57s, as group us journalists were confident we’d done a good job. But the teams Drivers had soundly beaten us all. Nico Rosberg did the challenge in 3m 15s, while Michael Schumacher did it thee minutes dead!

The job of the F1 engine builder and mechanic is a difficult and skilled one, the skills of the F1 driver are ever impressive and I’ll stick to drawing racecars and not working on them!

Mercedes AMG: KERS development

One of Max Mosley’s lasting legacies in F1 was the introduction of his vision of a green initiative in F1. As a result KERS (Kinetic Energy Recovery System) was introduced 2009, as part of a greater package of rule changes to change the face of F1.

KERS is a system which harvests energy under braking and stores it to provide the driver with an extra power boost each lap. A simple technical summary of KERS is here (https://scarbsf1.wordpress.com/2010/10/20/kers-anatomy/ ).

During the 2009 season McLaren were applauded for running Mercedes KERS at every race and it was widely reported as the best KERS in use that year. Along with a few other journalists, I was invited along to Mercedes AMG Powertrains in Brixworth, UK to hear about KERS development since 2009. With Managing Director Thomas Fuhr and Engineering Director Andy Cowell giving a presentation on the range of work Mercedes AMG does with its F1 teams.

Mercedes AMG Powertrains reside on the site that was previously Mercedes Benz High Performance Engines (MBHPE). Now renamed to reflect the wider application of the groups knowledge, both to uses outside F1 and to areas other than engines. Powertrain is a catch all term covering; engine, transmission, electronics and of course KERS Hybrid systems.

The company have built a purpose designed Technology Centre on the site, which historically was the Ilmor engine plant and positioned just a few miles from Cosworth in Northampton. Clearly this area has a rich seam of Engine knowledge.

Formed around three buildings the entire F1 engine and KERS development is carried out on site, only specialist functions such as the casting of the crankcases is carried out off site. Additionally other Mercedes AMG work is carried out here, such as the AMG E-cell car.

KERS 2009

Mercedes AMG (MBHPE as it was known then) developed their first KERS for 2009 in house. At the time McLaren were the primary customer for the system, although Force India and at the last minute Brawn GP were also customer teams that year. Force India had a chassis prepared to run KERS, but chose not to during the season. Brawn had a chassis designed before their switch to Mercedes engines, so their car was not designed to accept the Mercedes KERS.

In designing the system, Mercedes AMG had a specific requirement from McLaren. As the effectiveness of KERS was unknown, McLaren didn’t want to compromise the car if KERS was removed. So the system was packaged to fit into a largely conventional car. Whereas other KERS suppliers went for a battery position under the fuel tank, McLaren and Mercedes AMG placed theirs in the right hand sidepod. Low down and far forward, on the floor between the radiator and the side impact structures. The battery pack contains not only the array of individual cells, but also the pump and pipe work for its water cooling circuit. As well as the electronic interfaces for its control and monitoring. The assembly is around 7cm high, 12cm wide and 40cm long. The KBP is probably the single heaviest KERS component. In 2009 this sidepod package was acceptable as the teams were still on Bridgestone tyres and seeking an extremely forward weight distribution. Thus the 5cm higher mounting in the sidepod was offset by its forward placement.

Conversely the smaller Power Control Unit (PCU) was placed in a similar location in the other sidepod, ironically the PCU is around the size and shape of road car battery. This left the monocoque uncompromised, aside from the smaller cut out for the MGU in the rear bulkhead.

Then the Motor Generator Unit (MGU) is mounted to the front of the engine. This device generates and creates the power for the KERS. Its driven from a small set of gears mounted to the front of the crankshaft. the unit remains with the engien when the car is dismantled and is oil cooled along with the engine.

All of the components are linked both to the SECUs CAN bus and to each other by High Current Cable. The latter taking the DC current between the Batteries and MGU. With this packaging Mercedes AMG quotes the total system weight as 27kg.

Designed and developed by Mercedes AMG, but other partners were involved; the unique battery cells were supplied via A123 and the MGU was partnered with Zytek. Although the power control electronics were solely a Mercedes AMG in house development.

Through the 2009 season both McLaren drivers had a safe and reliable KERS at each race. The system was safe even after crashes and was fault free despite rain soaked races. Safety was designed in from the outset, all electrics were double insulated. Teams can also measure damage to the unit via accelerometers and insulation sensors, so any impact or incidental damage can be monitored and the car retired if the need arises. Additionally each cell in the battery has its temperature monitored. KERS batteries are sensitive to high and low temperatures, each cell needing to operate in a specific thermal window. Too low and the unit is inefficient and too hot and there’s the danger of explosion.

Perhaps the only criticism was the sidepod battery mounting, despite several incidents, this never put any one in danger, so this never proved to be an unsafe installation.

KERS 2011

For a variety of non technical reasons KERS was agreed not to be raced from 2010 until the planned 2013 rules. However this plan changed, but not before Mercedes AMG had made new strategic plans around KERS.

Mercedes AMG set out a longer term strategy to work on research for KERS in preparation for 2013, as well as working with AMG to develop the road car based E-cell technology.

(Link Mercedes AMG E-Cell chassis )

This changed when the plans for the 2013 engine were pushed back to 2014 and KERS was agreed to be reintroduced for 2011. Thus the 2013 development plans had to rebased and deliver a refined version of the 2009 KERS for 2011. Moreover there were now three teams to be supplied with KERS. There was no Christmas for Mercedes AMG staff 2010!

As a result of the research work carried out after 2009, Mercedes AMG now solely design, develop and produce the entire KERS package, aside from the Battery cells. So now the MGU is a wholly Mercedes AMG part.

With KERS effectiveness proven in 2009, it was possible to have the cars designed around it, rather than it be an optional fitment. So the packaging was revised and the entire system integrated into just two units. The MGU remains attached to the front of the engine, still driven off a spur gear on the nose of the crankshaft. While the KBP and PCU are now integrated into a much smaller single package and fitted under the fuel tank. The unit bolts up inside a moulded recess under the monocoque, the unit being attached using four vibration mounts, and then a closing panel and the cars floor\plank are fitted under it.

The 2009 battery pack (yellow) is now integrated with the power electronics (not shown) in a single unit under the fuel tank (red).

It’s this integration of the batteries and power electronics that has has really slimmed the 2011 system down. Mercedes AMG now quote 24kg the entire KERS, much of the 3kg weight loss being down to the reduction in the heavy power cabling between these units.

Not only is the packaging better, but the systems life and efficiency is too. Round trip efficiency stands at a stated 80%, which is the amount of power reapplied to the engine via the MGU after it has been harvested and stored. Improvements in efficiency being in both the charge and discharge phases.

Battery pack life was extended to as much as 10,000km, several times the 2009 predictions that batteries would need replacing every two races (2,400km). Over this period, the cells do not tend to degrade, as the team manage the unit’s condition (‘State of Charge’ & temperature) throughout the GP weekend to maintain their operational efficiency.

The 80hp boost KERS provides, stresses the engine. This was well known back in 2009, but for 2011 along with DRS the car can be several hundred revs higher than the usual EOS (end of straight) revs. Mercedes AMG quoted 15-25% more stress for a KERS and DRS aided lap, this needing to be taken into account when the team monitor the engines duty cycle, thus deciding when to replace it. Mercedes conducted additional dyno development of the engine being kept on the rev limiter to fully understand and counter this problem. This work paid benefits; Hamilton ran many laps at Monza bouncing off the rev limiter along the main straight, while chasing Vettel.

KERS in use

Although the max 60KW (~80hp) output can be reduced from the steering wheel, its normal for the driver to use the full 80hp boost each time they engage the KERS boost. With a reliable KERS, the driver will use the full 6s boost on every lap. Media reports suggest Red Bulls iteration of the Renault KERS does not use this full 60kw. Instead something like 44kw, providing less of a boost, but allowing smaller batteries to be used. The loss in boost being offset by the overall benefit in car packaging.

The driver engages a KERS boost either via a paddle or button on the steering wheel, or by the throttle pedal. The latter idea being a 2009 BMW Sauber development, where the driver pushes the pedal beyond its usual maximum travel to engage KERS. Nick Heidfeld brought this idea to Renault in 2011 and the over-extended pedal idea has also been used for DRS too.

Once the driver is no longer traction limited out of a turn, they can engage KERS. Usually a few small 1-2s boosts out of critical turns provides the ideal lap time. It’s the driver who has to control the duration of the boost, by whichever control. As with gear shift the drivers can be uncannily accurate in their apportioning of the boost around the lap. It’s suggested that the 2009 Ferrari system apportioned the duration of the KERS boost via a GPS map, the driver simply presses the button and the electronics gives them the predetermined amount of boost. This solution came as surprise to Andy Cowell, so one wonders if this is legal or perhaps if the report is true.

From on board shots, we’ve seen the steering wheel has an array of LEDs or numerical displays to show the driver the boost remaining for that lap. The SECU will have control code written to prevent overuse of KERS around a lap.

Typically the battery will hold more charge than a laps worth of harvesting\discharge. So that any unexpected incidents do not leave the driver without their 6s of boost.

In use KERS can be used in several different ways. When lapping alone KERS typically gains 0.45s per lap, although this varies slightly by track. Along with DRS is can boost top speed by 12kmh. As explained the driver uses a pre-agreed amount of boost, decided from simulation work done at the factory before the race. So the planned strategy of KERS usage will be used in practice, qualifying and in parts of the race. However in the race the driver can use KERS tactically to gain an advantage. Drivers are able to use more a KERS boost to either overtake or defend a position. One feature of 2011 along with the Pirelli tyres being in different condition during the race, was the driver’s freedom to alter their racing line and use their grip and KERS to tackle their rivals.

KERS future

KERS continues in its current guise for another two years, then for 2014 along with all new engine regulations there will be a new format KERS. Energy recovery will be from different sources, so the overriding term for the hybrid technology on the car will simply be ERS (Energy Recovery Systems). However KERS will still exist, harvesting energy from braking, but will have a greater allowance for energy stored and reapplied. But, there will also be TERS (Thermal Energy Recovery), which a MGU harvesting energy from the turbocharger. Overall ERS will provide a third of the engines power for some 30s of the lap. No longer will the driver press a button for their KERS boost, it will be integrated in their demand for power from the throttle pedal. The electronics will be constantly managing the Powertrains energy, harvesting and applying energy based on whether the driver is on or off the throttle. In 2014 Powertrains and ERS is set to become very complicated.

F1 2012: Rules, Designs and Trends

For 2012 we will have a raft of rules changes that will alter the look and performance of the car. For most of the new cars, we will immediately see the impact of the lower nose regulations. Then the big story of 2010-2011 of exhaust blown diffusers (EBDs) comes to an end with stringent exhaust placement rules and a further restriction on blown engine mappings.

Even without rule changes the pace of development marches on, as teams converge of a similar set of ideas to get the most from the car. This year, Rake, Front wings and clever suspensions will be the emerging trends. Sidepods will also be a big differentiator, as teams move the sidepod around to gain the best airflow to the rear of the car. There will also be the adoption of new structural solutions aimed to save weight and improve aero.

Last of all there might be the unexpected technical development, the ‘silver bullet’, the one idea we didn’t see coming. We’ve had the double diffuser and F-Duct in recent years, while exhaust blown diffusers have thrown up some new development directions. What idea it will be this year, is hard, if not impossible to predict. If not something completely new, then most likely an aggressive variation of the exhaust, sidepod or suspension ideas discussed below.

The most obvious rule change for 2012 is the lowering of the front of the nose cone. In recent years teams have tried to raise the entire front of the car in order to drive more airflow over the vanes and bargeboards below the nose. The cross section of the front bulkhead is defined by the FIA (275mm high & 300mm wide), but teams have exploited the radiuses that are allowed to be applied to the chassis edges, in order to make the entire cross section smaller. Both of these aims are obviously to drive better aero performance, despite the higher centre of Gravity (CofG) being a small a handicap, the better aero overcomes this to improve lap times.

A safety issue around these higher noses is that they were becoming higher than the mandatory head protection around the cockpit, in some areas this is as low as 55cm. It was possible that a high nose tip could easily pass over this area and strike the driver.

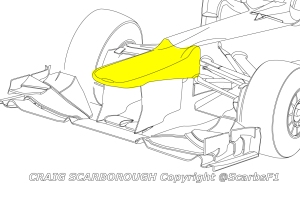

So now the area ahead of the front bulkhead must be lower than 55cm. However the monocoque behind this area can remain as high as 62.5cm. Thus in order to strive to retain the aero gains teams will keep a high chassis and then have the nose cone flattened up against this 55cm maximum height. Thus we will see these platypus noses, wide and flat in order to keep the area beneath deformable structure clear for better airflow. The radiussed chassis sides are still allowed so we will also see this 7.5cm step merged into the humps a top of the chassis.

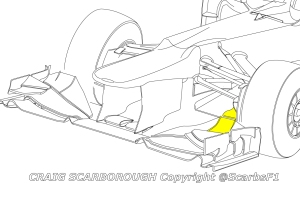

Areas below and behind the nose are not allowed to have bodywork (shown yellow in the diagram), so small but aggressive vanes will have to be used, or a McLaren style snowplough. Both these devices drive airflow towards the leading edge of the underfloor for better diffuser performance.

New exhausts

Having used the engine via the exhausts to drive aerodynamic performance for the past two years, exhaust blown diffusers will be effectively banned in 2012. The exhausts must now sit in small allowable area, too high and far forward to direct the exhausts towards the diffuser. The exhausts must feature just two exits and no other openings in or out are allowed. The final 10cm of the exhaust must point rearwards and slightly up (between 10-30 degrees). Allied to the exhaust position, the system of using the engine to continue driving exhaust when the driver is off the throttle pedal has also been outlawed. Last year teams kept the engine throttles opened even when the driver lifted off the throttle for a corner. Then either allowing air to pass through the engine (cold blowing) or igniting some fuel along the way (hot blowing). The exhaust flow would remain a large proportion of the flow used when on the throttle, thus the engine was driving the aero, even when the driver wasn’t needing engine power. Now the throttle pedal position must map more closely the actual engine throttle position, thus if the driver is off the throttle pedal, then the engine throttles must be correspondingly closed.

Blown rear wing (BRW): The exhausts will blow upward to drive flow under the rear wing for more downforce

Teams will be faced with the obvious choice of blowing the exhausts upwards towards the rear wing, to gain a small aerodynamic advantage, when the driver is on the throttle. These Blown Rear Wings (BRWs) will be the conservative solution and certainly will be the first solution used in testing.

However, it’s possible to be aggressive with these exhaust designs too. One idea is blowing the rear wing with a much higher exhaust outlet; this would blow tangentially athte wing profile, which is more effective at increasing the flow under the wing for more downforce. Packaging these high exhausts may cause more problems than gains. But last year’s exhausts passing low and wide across the floor suffered a similar issue, but proved to be the optimum solution.

A more aggressive BRW raises the exhaust and blows tangentially under the wing profile, which is more efficient

Even more aggressive solution would be directing the exhausts onto the vanes allowed around the rear brake ducts. If avoiding the brake cooling inlet snorkel, the fast moving exhaust gas would produce downforce directly at the wheel, which is more efficient than wings mounted to the sprung part of the chassis. However the issue here would be the solution is likely to be so effective, that it will be sensitive to throttle position and rear ride height. If these issues can be engineered out, then this is an attractive solution.

An extreme but legal solution is to blow the exhaust on the rear brake duct fins creating downforce directly at the wheel.

Wing ride height and Rake

With rules setting a high front wing ride height and small diffusers, aero performance is limited. So teams have worked out how to work around these rules by angling the entire car into a nose down attitude. This is known as ‘Rake’, teams will run several degrees of rake to get the front wing lower and increase the effective height of the diffuser exit. Thus the front wing will sit closer to the track, than the 75mm when the car is parallel to the ground. While at the rear, the 12.5cm tall diffuser sits an additional 10cm clear of the track, making its expansion ratio greater. Teams were using the EBD, to seal this larger gap between the diffuser and the floor. Without the EBD teams will have to find alternative way to drive airflow into the gap to create a virtual skirt between the diffuser and track.

Furthermore teams have also allowed the front wing to flex downwards at speed to allow it to get closer to the ground, further improving its performance. Although meeting the FIA deflection tests, teams are allowing the wing bend and twist to position the endplate into a better orientation, either for sealing the wing to the ground or directing airflow towards the front tyres wake. Both creating downforce benefits at the front or rear of the car, respectively.

One issue with allowing the wing to ride closer to the ground through rake or flexing, is that at high speed or under braking (when the nose of the car dives), the front wing can be touching the ground. This is bad for both aero and for creating sparks, which will alert the authorities that the wing is not its normal position relative to the chassis. So teams are creating ways to manage front ride height. Traditionally front bump rubbers or heave springs will prevent excessively low ride heights. Also the front suspension geometry runs a degree of geometric anti-dive, to prevent the nose diving under braking.

Last year we saw two additional solutions, interlinked suspension, where hydraulic suspension elements prevent nose dive under braking by displacing fluid in a hydraulic circuit one end of the car to the other end, creating a stiffer front suspension set up. This prevents dive under braking, while keeping a normally soft suspension for better grip.

We have also seen Lotus (nee LRGP) use torque reaction from the front brake callipers to extend the pushrod under braking, creating an anti-dive effect and prevent the nose dipping under braking.

An interpretation of the Lotus Antidive solution, using the brake caliper mounting to operate a hydraulic circuit and extend the pushrod (legally) under braking

These and probably other solutions will be seen in 2012 to maintain the ideal ride height under all conditions.

Front end

Towards the end of last year, front end aero design was converging into a set of similar ideas. Aside from the flexible wing option, already discussed above. The main direction was the use of a delta shaped three\four element wing, sporting no obvious endplate. The delta shape means that most of the wings downforce is created at the wing tip; this means less energy is taken from the airflow towards the inner span of the wing, which improves airflow at the rear of the car. Also the higher loading near the wing tip creates a stronger vortex, which drives airflow around the front tyre to reduce drag. Three wing elements are used, each being similar in chord length, rather than one large main plane and much smaller flaps. This spaces the slots between the elements out more equally, helping reduce airflow separation under the wing. More slots mean a more aggressive wing angle can be used without stalling. At the steepest outer section of wing, teams will mould a fourth slot in the flap to further manage airflow separation.

First introduced by Brawn in 2009, the endplate-less design is used as it’s more important to drive airflow out wide around the front tyre, than to purely maintain pressure difference above and below the wing. Rules demand a minimum amount of bodywork in this area, so vanes are used to both divert the airflow and meet the surface area regulations. This philosophy has now morphed into the concept, where the wing elements curl down to form the lower part of the endplate. Making the wing a homogenous 3D design, rather than flat wing elements and a separate vertical endplate.

A feature starting to emerge last year was arched sections of wing. Particularly near the mandatory neutral centre 50cm section of wing. These arched sections created elongated vortices, which are stronger and more focussed than tip vortices often used to control airflow. In 2012 many teams will create these unusual curved sections at the wings interface with the centre section.

Above this area, the pylon that mounts to the wing to the nosecone has been exploited to stretch he FIA maximum cross section to form the longest possible pylon. This forms the mounting pylon into endplates either side of the centre section of wing and along with the arched inner wing sections, help create the ideal airflow 25cm from the cars centreline (known as the Y250 axis).

Pointing a section of front wing profile at a suitable vane on the front brake ducts is one way gain aero performance.

In 2011 Mercedes GP used a section of the frotn wing to link up with the fins on the brake ducts, this created an extra long section of wing. Vanes on the front brake ducts are increasingly influential on front wing performance and front tyre wake.

Mercedes GP also tried an innovative F-Duct front wing last year. This was not driver controlled, but rather speed (pressure) sensitive. Stalling the wing above 250kph, this allowed the flexing wing to unload and flex back upwards at speed, to prevent the wing grounding at speed. But the effect altered the cars balance at high speed, and the drivers reportedly didn’t like the effect on the handling. I’ve heard suggestions that the solution isn’t planned for 2012.

Sidepods

With so much of the car fixed within the regulation, it’s becoming the sidepods that are the main area of freedom for the designers. Last year we saw four main sidepod concepts; Conventional, Red Bull low\tapered, McLaren “U” shape and Toro Rosso’s undercut.

Each design has its own merits, depending on what the designer wants to do with the sidepods volume to get the air where they want it to flow.

This year I believe teams will want to direct as much airflow to the diffuser as possible, Red Bulls tiny sidepod works well in this regard, as does the more compromised Toro Rosso set up. Mclarens “U” pod concept might be compromised with the new exhaust rules and the desire to use a tail funnel cooling exit. However the concept could be retained with either; less of top channel or perhaps a far more aggressive interpretation creating more of an undercut.

Part and parcel of sidepod design is where the designer wants the cooling air to enter and exit the sidepod. To create a narrower tail to the sidepod and to have a continuous line of bodywork from sidepod to the gearbox, the cooling exit is placed above the sidepod, in a funnel formed in the upper part of the engine cover. Most teams have augmented this cooling outlet with small outlets aside the cockpit opening or at the very front of the sidepod.

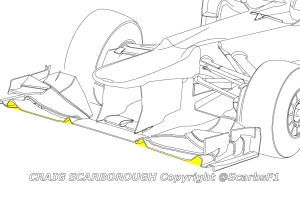

The tail funnel (light yellow) is a good cooling outlet method, as it reduces the size of the coke bottle section of sidepod

To let more air into the sidepod, without having to create overly large inlets, teams will commonly use inlets in the roll hoop to feed gearbox or KERS coolers.

Other aero

Even without the exhaust blowing over the diffuser, its design will be critical in 2012.

As already mentioned the loss of the exhaust blowing will hurt the team’s ability to run high rear ride heights and thus a lot of rake. Unobstructed the EBDs exhaust plume, airflow will want to pass from the high pressure above the floor to the lower pressure beneath it. Equally the airflow blown sideways by the rear tyres (known as tyre squirt) will also interfere with the diffuser flow.

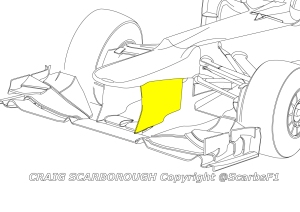

The Coved section of floor between the tyre and diffuser will be a key design in 2012, as will cold blown starter holes and trailing edge flaps

Before EBDs teams used a coved section of floor to pickup and accelerate some airflow from above the floor into the critical area between the diffuser and rear tyre. I predict we will see these shapes and similar devices to be used to keep the diffuser sealed at the sides.

Last year we saw teams aid the diffusers use of pulling air from beneath the car, by adding large flap around its trailing edge. So a high rear impact structure raised clear of the diffusers trailing edge will help teams fit these flaps around its entire periphery. Red Bull came up with a novel ideal by creating a duct feeding airflow to the starter motor hole; this improves airflow in the difficult centre section of the diffuser. Many teams will have this starter motor hole exposed by the raised crash structure, allowing airflow to naturally pass into the hole. However I expect some vanes or ducts to aid the flow in reaching this hole tucked down at the back of the car.

DRS was a new technology last year. We soon saw teams start to converge on a short chord flap and a high mounted hydraulic actuator pod. DRS allows the rear wing flap to open a gap of upto 50mm from the main plane below it. A smaller flap flattens out more completely with this 50mm gap, reducing drag more effectively than a larger flap.

As drag is created largely at the wing tips, I would not be surprised to see tapered flaps that flatten out at the wing tip and retain some downforce in the centre section. Teams may use the Pod for housing the actuators, although Mercedes succeeded with actuators hidden in the endplates. Having the pod above the wing clears the harder working lower surface, thus we will probably not see many support struts obstructing the wing.

Structures

Super slim gearboxes have been in vogue for many years, Last year Williams upped the stakes with a super low gearbox. The normally empty structure above the gear cluster was removed and the rear suspension mounted to the rear wing pillar. Williams have this design again for 2012, albeit made somewhat lighter. With the mandatory rear biased weight distribution the weight penalty for this design is not a compromise, while the improved air flow the wing is especially useful in 2012. So it’s likely the new cars will follow the low gearbox and low differential mounting in some form.

A lot is said about Pull rod rear suspension being critical for success. In 2011 only a few teams retained push rod rear suspension (Ferrari and Marussia). I would say the benefits between the two systems are small; pushrod trades a higher CofG for more space and access to the increasingly complex spring and damper hardware. Whereas pull rod benefits from a more aerodynamically compact set up and a lower CofG. I still believe either system works well, if packaged correctly.

At the front it’s unlikely pull rod will be adopted. Largely because the high chassis would place a pull rod at too shallow an angle to work efficiently. Regardless the minimum cross section of the footwell area, discounts any potential aero benefits. Leaving just a small CofG benefit as a driver to adopt this format.

Undercut roll hoops with internal metal reinforcement will be a common feature to drive airflow to the rear wing

Most teams now use a metal structure to provide strength inside the roll hoop; this allows teams to undercut the roll hoop for better airflow to the rear wing. Even though last year two teams followed Mercedes 2009 blade type roll hoop, for Caterham at least, this isn’t expected to return this year. Leaving the question if Force India will retain this design?

Electronics and control systems

The 2012 technical regulations included a large number of quite complex and specific rules regarding systems controlling the engine, clutch and gearbox. It transpires that these are simply previous technical directives being rolled up into the main package of regulations. Only the aforementioned throttle pedal maps being a new regulation to combat hot and cold blowing.

While I still try to crack that deal to make this my full time job, I do this blog and my twitter feed as an aside to my day job. In the next few weeks I plan to attend the launches and pre-season tests. If you appreciate my work, can I kindly ask you to consider a ‘donation’ to support my travel costs.